The plant sat in a ceramic pot on a high, high shelf in one corner of the office, stretching its limbs and runners the length of the four walls and dipping down to the floor in several places. I remember this distinctly. I spent many an hour sitting in that office in the English department, wondering if the plant was older than me or if its dominion over the room gave a deceiving sense of seniority.

Sometimes when my professor would speak enthusiastically about a book, he would rise up in his chair and get smacked on the head by the cascading leafy runners. We met once a week through my senior year to discuss my thesis paper. I’d shown up to campus for my admitted students weekend four years earlier with a worn copy of The Essential Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe in arm, so my gin-fueled thesis paper on Poe, materialism and metaphysics felt like a comforting oeuvre as graduation neared.

My professor, Dr. Burt, was (and I’m sure still is) an eccentrically brilliant man with what seemed to me at the time half a dozen post-bac degrees from Yale. He’d often tell a joke during his lectures that escaped the class, collapse into a moment of laughter, and close his eyes and hands together to his face to recompose before resuming. He was the first person I’d seen take a deep breath in a stuffy academic room.

Poe is someone you need to read with your cereal box-prize mystery decoder ring in hand, he said. When I wasn’t ogling the plant during our thesis meetings I was picturing an Inspector Gadget solution for my reading material. So much of my university years found me searching for a decoder ring to make sense of it all – and not just in class. On a full-ride scholarship to a school 3,000 miles away from home, I had become too precocious for my sleepy hometown, but was still too parochial for the metropolitan future I wanted so badly. It’s a problem that so many people who are among the first in their families to go to college experience, and it doesn’t go away after you get your diploma.

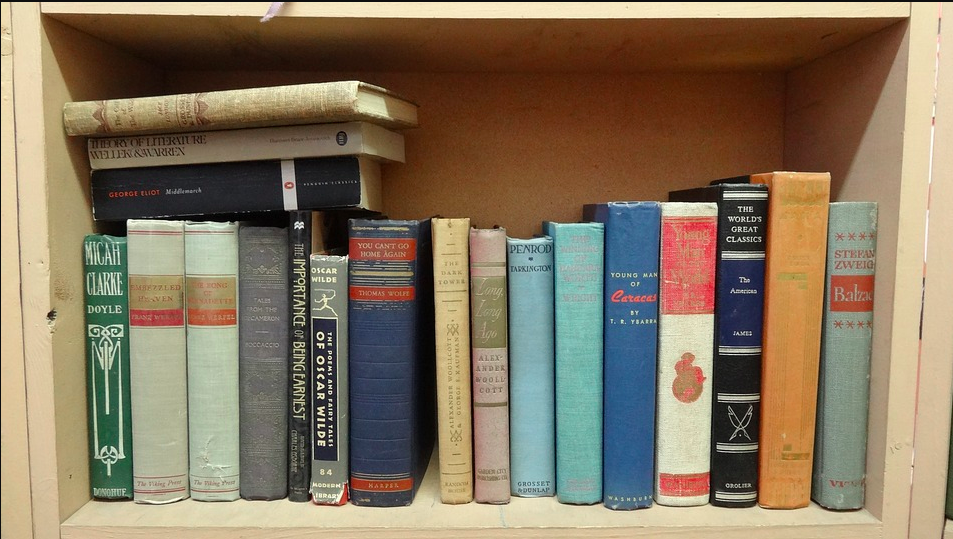

Dr. Burt told me probably as many times that year as the plant tapped him on the head that there is a book I should read, and it’s called Middlemarch by George Eliot (a woman). Of course, the book was 800 pages and college distractions abounded, so I didn’t read it then. A couple years after graduation, I was in the middle of a godforsaken Louisiana swamp with my Army unit shaking from hunger, exhaustion and impatience when I fished Middlemarch out of the Ziploc bag I’d packed it in to keep it dry in my rucksack. I hadn’t been able to feel my toes for several days and was feeling sorry for myself, so I read. And I couldn’t put it down.

Those 800 pages and lots of ridicule from passing soldiers later, I felt I’d been smacked on the head by my professor’s ancient office plant. There is no dramatic ending! There is no sweeping resolution! There is a pithy conclusion and here it is. Our heroine, Dorothea, has survived a marriage for the sake of piety and prudence, to a man much her senior and entirely too boorish to deserve her. As his health declined, she fell in love slowly and tenderly with young man of common pedigree in the novel’s Victorian society setting. Dorothea’s first husband dies (spoiler, sorry), and on his deathbed he stipulated in his will that if she marries her new love, she will forfeit the inheritance of his wealth. It’s a scandalous place for a woman to find herself in this era, but she chooses love. In remarrying, she suffers the judgment of her community atop the loss of a fortune.

George Eliot, whose real name is Mary Ann Evans, has the audacity to bury the most precious nugget of her story on its last page as she bids Dorothea farewell. Emphasis mine:

Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of imperfect social state in which greater feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. … But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs. The end.”

Unhistoric acts. I read almost a thousand pages to get here – that is a historic act, for me at least. But in the years since I read the book, I’ve often thought about George Eliot, living faithfully, and committing unhistoric acts for the betterment of others. The irony of the didacticism here is that the greatest services are not things you set out to do. They’re things you do one step at a time, from moment to moment but consistently, out of a genuineness of character and a mindful goodwill. They’re the things that will get us through crisis.