I spent most January nights in a sleepless haze crowded by waiting. I wasn’t quite sure what I was waiting for, perhaps for summer to come, for my shivers to stop, and long evenings sitting at the porch, top off, to begin. Perhaps I was waiting for the day I could stop saying ‘I’m a student’ and say instead ‘I’m working’. Or maybe none of that mattered. Maybe my restlessness was only a result of the shortening gap between the date I’d see my parents again and the nights I refused to close my eyes.

I knew.

When I was young, there was a period of time between the ages of four and five when I refused to go to sleep because I was too afraid I’d miss something. Like a shooting star. Like a Blood Moon that comes only once every two or three years. Like my dad on his way to the hospital.

I knew.

I’m not quite sure when I stopped battling with sleep every night. The anxiety eventually faded away when my four-to-five-year-old body became too exhausted to handle anything more than a normal day. Until nights of January 2021 when, like my younger self, I gradually started feeling the need to stay up a little longer, to wait for my phone to vibrate one more time, for the next news story to pop up. For the next phone call.

There was no phone call that night.

During those late January dawns, I laid between warm covers staring at the ceiling in a once stranger’s bed, in a once stranger’s house that I came to call my family in less than a year— my second family anyway— and pictured my first one. I’d think of the times we’d stay up late talking about everything and nothing while mom sipped her tea and dad sipped his red wine while eating his cheese-and-cracker dinner. My grandmother would eat nothing. Two or four ounces of whisky was a better dinner, ‘to warm the soul’.

I spent the weeks before it happened planning their next vacation. I hadn’t seen my parents in more than two years— we had been spending time together only through pixelated screens and minute-long voice notes that I rarely listened to. They weren’t the same as them. They would come for my graduation and stay more than a month. Dad bought two round tickets: Caracas to the Dominican Republic, the Dominican Republic to Orlando. Multiple airlines. May 21st to July 6th. I wished they were a one-way ticket.

Most nights turned into a dimly lit room, toss and turns in my too-warm, too-cold empty bed while I wrote down the places I wanted my parents to see for the first time. I scribbled them down on post-it notes I attached to my pocket journal: I’d impress dad with nice bottles of wine and restaurants where he wouldn’t even get a glimpse of the check. I’d take mom to the dozen plant stores I had discovered and buy her flowers every week. I’d make her teach my new mom, my Llama, how to make orchids bloom every spring. I would tell dad I loved him for the first time. I’d let him put his hand on my shoulders without pulling away.

I’d be more patient around the two of them.

I knew.

February 16th I found a two-bedroom historic house for rent in E Taylor Street, Savannah where we’d stay to celebrate my graduation. Weathered brick walls, a wide backyard big enough to throw a party every night without being heard, antique-rusted benches, and a grill right by the corner of the yard where I knew my dad would try to make his famous burgers every night. I planned to eat one without complaining this time. It was the perfect place for mom and dad to be safe, away from crowds, enjoying a dream come true— the four of us together.

The phone rang and rang. “Larry Hernandez, ahora no puedo contestar. Después del tono deje su mensaje.”

My mother’s phone rang and rang.

The monotonous tone pierced my ears. I knew. I tried once again and while it rang, while it continued to hurt, convinced myself I was being negative— bad internet was more common than a sunny day in Caracas.

I wasn’t.

Stubbornness is a trait that runs thick and big in the family and my dad and I were certainly the biggest carriers. When he was young and deviated his nasal septum, he refused to get it fixed claiming ‘it was nothing serious’, that ‘it didn’t hurt’. Ten years later when his sleep apnea was so bad we made fun of his snores by nicknaming him ‘The Lion’, he dismissed surgery because he had to shave his iconic French mustache. God forbid he’d lose the trait that made him famous. This year, when both of my parents got sick with COVID, he took her to the hospital to get a medical check. He waited outside. He was feeling great. He didn’t need one. He bought her sushi the next day when she didn’t feel like eating. My dad’s attention, or perhaps the sushi, made my mom gain back her spirits.

His spirits were never there.

On the night of February 15th, he silently struggled for breath as my mother frantically drove around in his old Land-cruiser Toyota from one hospital to another looking for a vacant bed for him. He barely made it in time to the emergency room. He’d been in silent hypoxia for days—blood oxygen levels dropping as fast as the rhythm of his breaths without him realizing. Without anyone realizing until it was too late. By the time he got in, he was at 50 percent. His skin, usually blushed under his mild tan, was paper white. Turning translucent green.

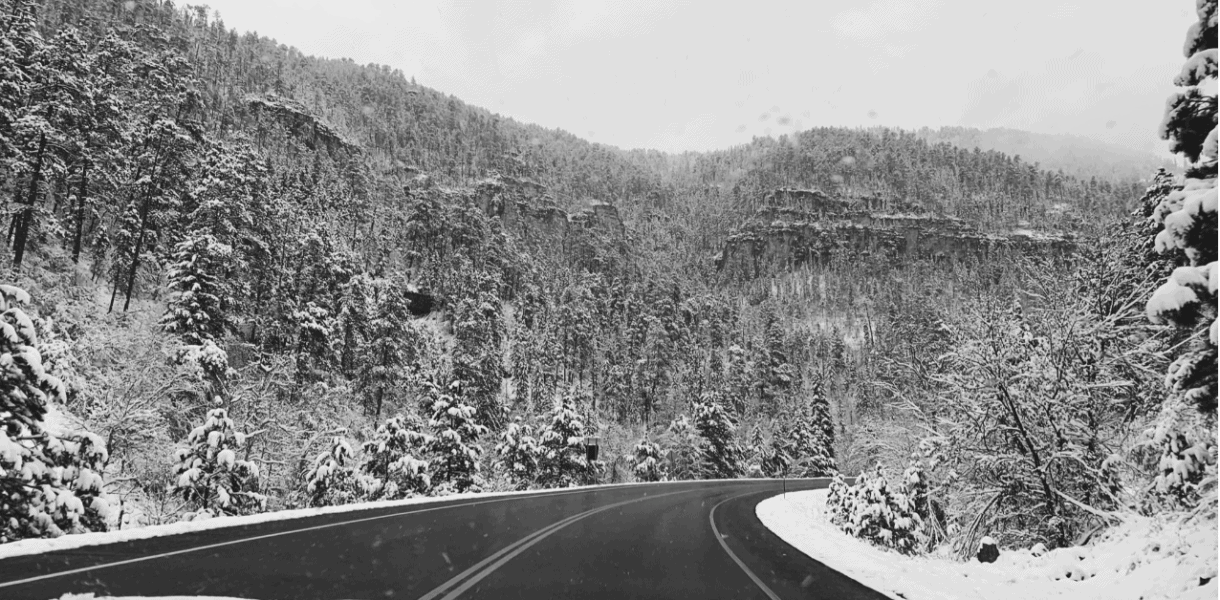

February 17th the doctor told us his lungs were white. The scan came back white. And for a second I thought white was purity. White should’ve made me feel as calm as watching the snow slowly pile on the ground. And I did. I stood by the window thousands of miles away from dad watching as snowflakes dropped down steadily and immediately melted on the pavement. Gray. They turned gray. He couldn’t breathe. Normal lungs are supposed to be dark, full of life and activity. He couldn’t breathe.

I couldn’t either.

February 18th I considered texting him I loved him but sent him pictures of our little house downtown instead. I didn’t want him to think I was losing my stubbornness, turning soft just because he wasn’t feeling well. I didn’t want him to believe he was close to dying. He wasn’t. He couldn’t be. He was always the strongest man in the room— twirling his already perfectly arranged mustache as he walked around and led people with a warm smile. I never thought a virus could take that away from him. I’ll tell him I love him when the white in his lungs becomes as dark as the coffee I’ll make him every morning.

I should have texted him I love you. I texted him be strong instead.

On the morning of February 19th, I changed my mind, let go of my pride, and wrote down how much I missed him. I missed the sound of his dress shoes knocking on the hardwood floors every morning before I went to school. I missed the weird face he made when he was really excited or proud of what I’d tell him. I missed his creative inputs and strong critiques on my work. I missed his waffles every Sunday morning, our hikes up the Avila, our afternoons sipping marron con leche at Cine Cita.

His lungs kept getting whiter. The snow kept falling down and turning my backyard white, then gray. I wanted gray.

He died close to five in the afternoon of February 19th.

My message remained un-sent. Unread.

I knew.

Nineteenth of February, 2021 — one month before his 26th anniversary (31st he would have argued. They had been together 31). Three weeks before my college graduation and three months before he came back to me.

I never told him I loved him.

He never got to try my good, black coffee.