It was 2005 and my life was all over the place. I had my apartment in Manhattan but was living in Truman Annex in Key West with my husband. Each morning, the roosters greeted us with their spirited cries as a warm breeze floated in through our balcony terrace. I felt as if I had found my own private paradise. We shared sunsets at Mallory Square, dinners out on Duval Street, or at my favorite Schooner’s Wharf Bar on William Street. I couldn’t imagine any other reality at the time.

I worked my corporate gig by day and two nights a week I taught writing workshops at the Tropic Cinema, which at the time was a new movie theater that showcased independent, international, and classic films in Old Town Key West. The pulls to relocate to Key West were tied to my having literary agent clients who resided there and my graduate work on Hemingway. I had spent weeks on the island during the Hemingway Days Festival each July and the Key West Literary Seminar each January for close to a decade. Key West had become a second home to me. When my husband had insisted we leave New York City, given the choice between Los Angeles and Key West, it was an easy decision for me.

My writing workshop crew was a substantive part of my Key West existence. After years of teaching writing in New York City, it felt expansive to work with a group on an island. The cast of characters always kept me on my toes: the elderly former nun who currently resided in the nudist colony; the grandmother who brought her high school-aged granddaughter to class; the World War II vet/shop owner who wrote books; the Boston model who married a Spaniard and brought him to the US; and Marta from New York City – artist, actor, multi-millionaire – who looked me in the eyes one night and said, “You never know who is going to change your life,” later telling me that I was that person for her. I had learned earlier in my career about the power of writing, and its ability to let others into the nooks and crannies of one’s mind. Writing, I understood, was something that needed to be nurtured and respected, and I was clear I needed to speak from a genuine voice both when it came to my own writing and that of others – a voice that was gentle at times, but unafraid to be critical with an intent to help others to improve, too.

Regardless of all that was going right in my life during that time, I was unsure of my future with my husband. He was volatile, off center, and his gambling had taken a toll on me, on our relationship, and was once again dragging him down into the pit he had lived in for so much of his life. He was frequenting 12-step meetings, as he had in New York, as he had for most of his adult life. He had his story down pat and enjoyed sharing it with new audiences – something of the thrill factor and also his desire to perfect it. He liked to tell others – myself included – that we were unstable, insinuating that he had it all figured out, but the truth was, he was weak and always looking to blame someone else. I had come across a children’s book many years back called, Someplace Else, about a little boy who was always wishing he lived somewhere other than where he was at, and strangely, I thought of it as fitting for my husband. He was always striving to be someplace else, where he felt he wouldn’t succumb to pressure, to gambling, to the highs and lows it took him through.

By nature, I am a stick-with-it person; I believe in the power of transformation and I also ascribe to the universe putting us in situations from which we can grow. I believe that much of life and overcoming hurdles has to do with perseverance; I believe that most people quit things in their life too soon, and that staying with situations is where and how the growth occurs. But I also believe that there comes a point when we must make decisions to save ourselves from the dark pits of life. David Swenson’s mantra, “there’s the fear that keeps you alive, and the fear that keeps you from living your life,” was a sentiment I pondered often.

My dear friend Michele had been in India for months, setting up back offices for JP Morgan. She was stationed in Mumbai, at the JW Marriot specifically, where she and a host of JP Morgan-ites were living. As her assignment was wrapping up, she decided to stay on for a bit on holiday, and had convinced me to join her. With my husband in Los Angeles spending time pursuing his career options, I opted to get away. But it wasn’t without its own complications. A monsoon had recently hit Mumbai resulting in deaths and devastation, so that travel there was not ideal, but my friend reassured me it was okay – she was safe.

The adventurer in me opted to board a plane from New York’s JFK airport, and some twenty hours later, I arrived in Mumbai at 2 am, to be greeted by Michele and one of her colleagues at the airport. That first night was like a dream: back at the hotel, we sat around at the all-night buffet, drinking red wine, discussing the nuances of our lives over the last few months, and eating snacks. Eventually, we went to sleep and over the next few days, as she finished up her work and I acclimated to India – the sights, 24/7 sounds of people, rickshaws, smog, and charcoal-aroma – we made our plans to travel to Mysore, which involved a flight to Bangalore followed by a five-hour drive. When we weren’t in planning mode, we spent time at the gym on side-by-side treadmills, clocking miles and gossiping away while we watched 1980 movies on the large screens all around us. We lounged at the wedding-like 24/7 food buffet, picking at the endless salads and fruits and hanging out with the JP Morgan crew.

In India I felt farther away from everything in my life than I had ever felt. It was a delicious sense of floating. Our journey flying from Mumbai to Bangalore filled me with wonder: India was a curious mix of old and new. At the airport, the bathrooms consisted of holes in the ground with places for one’s feet, and outside of the airport, the mass of people on the streets was overwhelming. New York City suddenly loomed a small place to me. Our five-hour buggy ride on rickety dirt roads headed to Mysore made me sure that our deaths were imminent. Our driver drove recklessly, barely missing hitting cows and people, assuring us all the while, “you don’t worry.” Somehow, we arrived in one piece at our destination: Mysore, the home of Pattabhi Jois, the guru of our beloved ashtanga yoga.

Once in Mysore, the rickshaws beeping at all hours of the day and night, the mud- floor chai stalls, the cows lining the road, the university students parading the streets, transported me to another dimension. I was reading Michael Cunningham’s novel, Specimen Days, at the time and I remember thinking how fitting that it was.

Our hotel was a palace of sorts, but the pace of those who worked there was slow. When it came to service and amenities, they didn’t seem quite ready for American guests, let alone New Yorkers. It’s worth noting that prior to our departure, Michele and I put together a three-page handwritten list with detailed items on how the hotel staff could improve their policies and offerings to make their guests’ stays more enjoyable. Each night, the hotel staff draped our bed frames and pillows with fresh jasmine – the fragrance so poignant and sweet that it is still vivid to me, even now, so many years past. It’s the smell of possibility, of serenity, of tucking oneself away to renew and refresh.

A few days into our Mysore adventure, there was a message from him, my husband, on my cell phone. He was not aware of my venture to India. “I miss you. I want to be with you—I’m coming back to Florida. Please call me.” If I had been in Florida, I would have quickly erased the message and gone on with my day – his sentimental mood swings had grown old to me. But in India, so far away, his message made me waiver. Maybe we were meant to be after all. At my spiritual core, I believed that unions were not all about choice, but about the universe putting you in the proximity to the person you were meant to be with. I was going to call him, tell him I was in India, that I missed him. “Wait,” Michele advised. “Give yourself 24 hours. Wait and see how you feel tomorrow.” Sure enough, the next day, I was glad I had waited; the momentary spell his longing placed on me was over.

A week into our Mysore adventure, we had a routine: we awoke before daybreak and drank masala chai delivered to our door. We bickered with the hotel staff regularly when they got our masala chai orders wrong and brought it at 4 am or 5 am versus our 4:30 am sharp directions. But days later, when we learned that the waiter who delivered our chai was a university student with a mother who had fallen ill to tend to, we no longer complained.

When first light began to peep through on our balcony, we covered ourselves with bug spray – we had stopped taking the prescribed malaria medication a week into our journey due to hallucinations and overall feelings of malaise – and ventured to the university track, which was packed with men, women, and children of all ages. At the track, we joined the families in walking a few laps prior to venturing to the Mysore Mandala Yoga Shala, where we practiced Mysore style ashtanga yoga each day with Sri V. Sheshadri as our guide, and his son, Sri Harish, assisting. Mysore ashtanga is a practice crafted by Sri Krishnamacharya and passed down to Sri Pattabhi Jois. Sheshadri was also heavily influenced by his guru Sri BNS Iyengar. I had practiced with Pattabhi Jois dozens of times during his visits to New York City. The most memorable experience was in the days following 9/11, which coincided with one of his visits. For those of us lucky enough to be in that yoga room on those days, the love we experienced was profound and empowering. In a world in which mass destruction was possible, it was a reminder that expansive love was another option. Michele and I had opted to study with Sri Sheshadri in India versus our beloved Pattabhi Jois, as our NYC teacher had shared that Sri Sheshadri had a magic all his own.

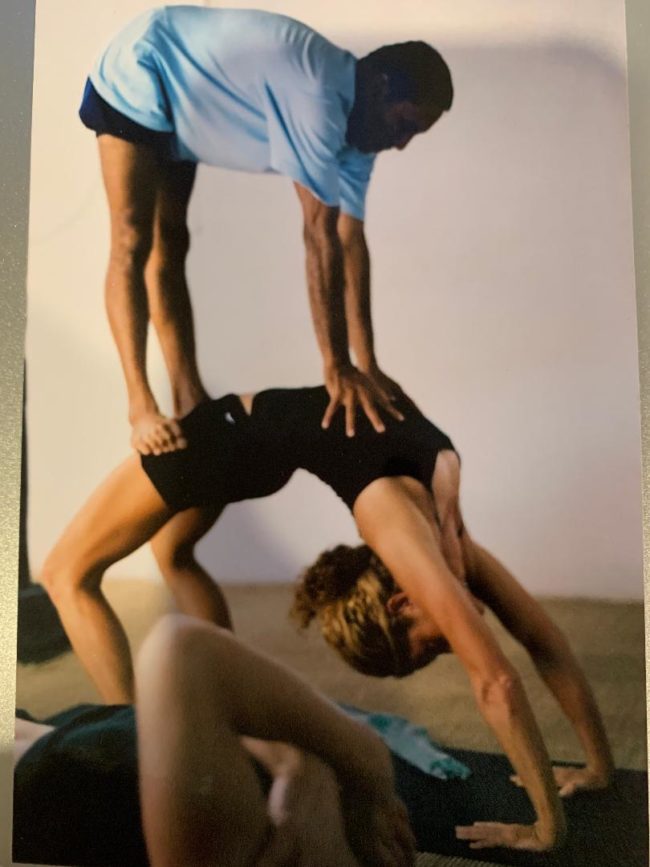

Five-feet tall and thin with a muscular build, Sri Sheshadri was one of the most powerful forces I had ever encountered. His demeanor was both welcoming and fierce; he evaluated his students’ practice with the eye of a fine craftsman, assessing each practitioner’s capabilities and where one needed assistance. He always knew when to assist and when to leave you to negotiate a pose on its own. After a few days under his tutelage, he never hesitated to pull my arm so far out of the socket that I was sure it was dislocated, with an intent to wrap it into a pose. Backbends were a unique experience: by the end of my first week, Sheshadri was standing on my thighs and grounding my legs as his hands eased the arch of my back open in ways I would have deemed impossible. There were the days he used a towel to drop me back into backbends, asking me to reach, to trust, to bend and flex in ways that afterwards made my body feel as if it was weightless, floating. There is a magic in trusting, in letting your body open, in becoming free of fear and working past barriers. On the days the shala was especially crowded with practitioners, his teenage son would walk around assisting us in our ashtanga practices, and although he was young, from his touch, his confidence, and his profound skill, it was clear he was the next master-in-training. Afterward, we meditated and rested before we socialized with the other yogis – some from the US, some from Europe, a few from Australia – and then made our way back to our hotel for our breakfast of papaya and spiced chai and a medley of Indian treats, during which time we devoured the India Times and read aloud the “Sacred Space” section to one another.

There is a poverty to India that is palpable in the barefoot children who run along the streets, the men who asked for money at the markets, and those that make tea at chai stalls to sell for change. And yet, there is a sense of unity, of community, of acceptance, that left me with a sense of longing. Generations of women walked along the streets chatting with one another, or sat together on their stoops, looking out at the world. There was a peace regardless to the constant noise, and yet, I often felt desperate, unhinged, when I considered their lives. I didn’t see their way out or through this small southern Indian town with its array of universities and implicit male dominance. Would any of the young women in Mysore ever be more than wives, mothers, and work in family shops? Would any of the men ever earn a solid living? But perhaps that was my own delusion. Perhaps those who lived in Mysore were content; perhaps they did not wish or want to leave their town for more lucrative lives and careers. During my time in India, I tried to discern if those we interacted with were happy or longing, but I couldn’t tell. It seemed more likely that they viewed us visitors as lost and unhappy, having to travel so far to their little town in search of something we couldn’t find in lush America.

In India I had time and space. I no longer felt rushed to make decisions. I began to unwind and unpack the elements of my life: work, relationships, family, my creative endeavors. What did I really want? How was I planning to achieve what I sought? And what was behind my wants? Were they shallow desires, or something deeper rooted? Who was I when I was stripped of time and place and people? In Mysore, I was steeped in discovering those answers, but most often, I was immersed in being versus thinking. There were hours each mid-morning when there was nothing to do but sit on our balcony and read, write, stare into space. Afternoons we visited Ayurvedic clinics where we tried out an array of services – oil massages and saunas and facials – and some days we visited with the Missionaries of Charity and helped with feeding the destitute women who lived at the missionary or just walked through their bunks to spread cheer.

One day at the home, the nuns charged Michele and I to give out the weekly peas and rice rations to the hundreds of local women who relied on the sisters for their survival. The missionary workmen piled mountainous stacks of peas and rice beside us and gave us shovels. As we scooped the peas and rice into the women’s sacs, one by one, the women fought us, motioning for us to give them larger servings, or trying to put three bags in front of us to fill instead of the two they were allowed. There were tall women, short women, sturdy women, frail women; children dressed in ragged, holey clothes ran around the missionary grounds while their mothers and grandmothers waited in line, swatting away flies. I didn’t know at the time that day would permeate in my brain, become a point of reference to me, a reminder that we take so much for granted in our abundant American lives. A reminder that we are all here to help one another. A reminder that there is a bottoming out of life that doesn’t mean we are any less valuable and deserving, and that kindness and helping those in need is not just an act of good faith, but the most important acts of our lives. We are one another’s keepers, united by our breaths, experiences, the universe.

Evenings, Michele and I sat in Café Day – Mysore’s version of Starbucks – and nibbled on chocolate chip cookies and lattes, and laughed and talked about whatever topic gripped us – incidents with new friends from the yoga shala, friends at home, our lives, relationships. Within a few weeks, I was freer, happier, and calmer, than I had ever remembered being. There was a rhythm to India that nurtured me, a timelessness that made me feel unrushed, so that I was able let go, not focus on my to-do lists. For the first time in a long time, I was not clinging to my marriage, to my idea of how my life should be, I was not praying for things to be other than how or what they were. India in many respects initiated me into reality, and reality, I realized and accepted, was okay. Better than okay: reality was perfect. I was able to see and know that everything was exactly as it should be. Over the course of a month, I was filled with an abundance of love and joy that didn’t relate to any one thing, but everything. I was grateful to be alive, and the gratitude emanated from my core versus anything external.

Our travels were not without tribulations: two women traveling alone in Asia, there were moments of danger. There was the afternoon a middle-aged indigent man exposed himself to us at the monkey gardens, following us around, before he ran off into the forest; the night a young man followed us at close range as we opted to walk back to our hotel, resulting in us eventually running to a rickshaw in the middle of traffic, and pleading with the rickshaw driver to drive us home. Regardless of our less-fortunate encounters, India made me feel invested in the good in life and people. I am not sure if it was the intense daily yoga, being so far from everything in my life, or simply a new-found acceptance that was beginning to cultivate within me, but in India, I grew more accepting of my own short comings, which made me more compassionate in regard to other’s shortcomings. In India, my empathy for both myself and others heightened.

When I returned to Florida, I had planned to stay with my parents for a week on the mainland before I ventured back to Key West. My mom was to undergo hip surgery, and with Labor Day weekend approaching, it made sense. During that time, there were hurricane warnings, and then they hit: first Katrina with its shattering force, then Hurricane Rita added to the destruction, and eventually, Hurricane Wilma. Leaving my parents’ house to return to Key West or venture to New York City was no longer an option. Gas, flights – all were unattainable. We watched on television as Louisiana and bordering states underwent mass destruction, and when we lost electricity, we listened to portable radios. As the days went on, everything in south Florida remained at a standstill. With no other options, and my timeline for leaving south Florida unsure, I set up shop to work from my parents’ house.

Adapting back to the US had its challenges, largely because I was displaced, and I had unfinished business to address. I was clear that I was going to get divorced, which meant difficult conversations with my husband, his moving out of our place in Key West, my moving from Key West, and my imminent return to New York City. But the hurricanes threw me off track, providing me with more time to consider my next steps. I was grateful for the delay in some respects. It overwhelmed me to create so much change. I had to rehearsed in my mind what it would all feel like – signing the divorce papers, packing up, moving on with my life. I wasn’t sure where it was best for me to be. Key West certainly had it its perks with sunshine and beaches and the overall island flavor. But New York City was home, and it was where all my friends were.

Time did its thing: months passed, and by the end of January, I was divorced and gearing up to move from Key West. Whenever I feel that I hold the reigns of my life, I am reminded that I am a puppet, with life as the master. By April, I moved up to Highland Beach, a dozen miles from my parents’ home, opting to put off my return to New York City for a bit longer. I had made several friends in south Florida, largely from being stuck there after the hurricanes, and some of my closest friends from New York had also moved local to my parents. My intuition must have known something that reality had not yet disclosed, as later that month, via annual blood tests, my mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer. My mother, who was my best friend, who always asked the pivotal questions in my life: “Is that what you want?” “Is this how you want to live?” now had a life sentence. The blow hit like a stick of dynamite, shattering my past, present, and future all at once.

My life didn’t get worse after India, but it shifted. I began to accept that sometimes things just were, and that life events didn’t have to follow any rhyme or reason. I was faced with a new level of soul searching that asked me what I needed each day to take care of myself, to love others, and not to hate the universe for the fate it doled out. I had to figure out what the minutes, hours, and days meant to me. I had to learn how to get through them all, how to smile and be open to love even when I felt disillusioned – even when I wanted to cry and scream. I learned that it was up to me how I reacted to anything and everything. I could find the good, or drown in the bad. And even if I found the good, I was allowed to hurt and cry and wonder and wish, as long as I remembered not to blame others, not to lose my love and gratitude for all the good that was, and to pick myself up at some point and keep going. Because that is what life did – it kept going.

Over those years in which we witnessed my mother’s decline, in which life external to the planet of my family went on, I often thought of my time in Mysore and practicing ashtanga with Sri Sheshadri, and the love he endowed upon my spirit and flesh to help me move in ways that were counterintuitive – in ways that looked painful to the inexperienced eye – and yet were cleansing and grounding, and over time, opened me up to endless possibilities. I thought of those weeks which turned into months after the hurricanes when I got to live with my parents, and relished how lucky I was to have that time with them in my adult life. It was the last time we had together when everyone was still healthy and carefree. The universe and its mysterious ways were mine if I accepted them. If I didn’t oppose the chain of being, then everything was on my side, propelling me forward, into, beyond, regardless of the challenges I met along the way.

When we were leaving India, softer and perhaps more mindful versions of ourselves, Michele and I had sat together in the London airport lounge, laughing over anything and everything as we picked at snacks and tea. Then, hours later, immersed in conversation, we heard and then recognized our names being announced in the lounge – our flights were in final boarding. It was last call. It would have been so easy to stay, to let the holiday continue, to put off returning for one more day, but we grabbed our things, and ran off to make our flights, to rejoin our lives, to return. We rushed forward in the airport, our hearts and minds open, into all that was to be – imperfect and heart breaking, and wonderful, too.